Sarah Whalen

The USA claims it wants to establish a fair, responsible and democratic system of government in Iraq. Traditionally, this would mean a speedy election of Iraqis, by Iraqis, and for Iraqis. But the Bush administration has something different in mind than Iraqis controlling their own destiny by one-man, one-vote. Under its “transition plan,” the current hand-picked Iraqi Governing Council would first choose delegates to an interim national assembly at 18 provincial caucuses. This assembly would then hold power indeterminately until a permanent constitution could be written, and who knows how long that might take? And then, ideally, elections for a permanent form of government could take place the following year.

Kofi Annan’s assessment of prospects for democratic elections in Iraq looks like a fore-ordained decision in favour of continued USA interference in the country.

To even further delay this “democratic” process, the USA now seeks to involve the United Nations, a body it previously wholly shunned, in its “transition planning.” Doubtless, the Bush administration was much taken by U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan’s declaration that general elections in Iraq would be impossible to hold in a timely manner: “We do not have enough time to organize free and just elections for the transitional government,” Annan recently proclaimed.

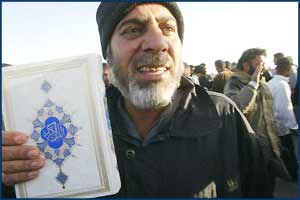

Who has emerged in Iraq as the champion of speedy political freedom and choice? None other than the Grand Ayatollah Ali Al-Sistani, Iraq’s most important Shiite cleric, leader of Iraq’s largest religious group. Tens of thousands of Iraq’s estimated 15-16 million Shiites (out of a total population of 25 million) have marched in Baghdad and in Basra this month, reiterating Al-Sistani’s demand that general elections be held immediately. Public opinion polls indicate that elections would strongly favor Shiite religious groups, which are really the only well-organized civil groups consistently functioning in postwar Iraq. Iraq’s Sunni and Christian minorities are said to fear that speedy elections will result in sectarian conflict.

Clearly, for the USA, democratic “stability” is clearly tied to diminutions of passions and careful selection of interests - the two main factors that drive all electoral politics in general. In delaying truly democratic elections in Iraq, the USA reveals how far removed it has become from its own democratic origins, which commenced not with the colonial revolution or its 1776 Declaration of Independence, but much earlier - 1620, to be precise, when a small group of conservative religious fanatics, hated and reviled in their own European countries, crossed the vast expanse of the Atlantic Ocean and arrived at Plymouth, Massachusetts, where the 99 survivors “stayed.”

Their original destination had supposedly been the northern part of the then-British territory of Virginia, roughly where New York City lies today, but the fanatics sailed even further north, beyond the Virginia limits.

Set in Stone. The religious ‘democracy’ of the Pilgrim Fathers resembled Shiite plans for Iraq, but it became the cornerstone of USA’s democratic culture.

The reasons for this are in historical dispute. The fanatics themselves officially claimed to have gotten lost or misled by their captain, but scholars now think that they intentionally sought to avoid not only the grasp of the British government and its established religion, but to do something so simple and yet so extraordinary for their time - “to live as they wished,” writes historian Eugene Aubrey Stratton, “and take orders from no one.” Their notion for independence was borne not of any inherent unity, but from this tiny group’s inherent divisions and fractiousness. Thus, “it was thought good,” wrote one fanatic, “that we should combine together in one body, and to submit to such government and governors, as we should by common consent agree to make and choose.”

What these fanatics, whom we now call the Pilgrims, desired and achieved was nothing less than a highly conservative, rigid religious state. What is worth looking at more closely as democracy is pushed further away from fruition in Iraq is that from the Pilgrims’ desire to live wholly under God’s command was born the Mayflower Compact, which stated essentially that all individuals agreed to submit themselves to majority political rule.

Like the modern Iraqis, the Pilgrims’ were an unstable society in a harsh environment. Three months after landing in America, half the Pilgrim settlers died, and many others became wretchedly ill. Facing critically low food supplies, daily deaths, and untold dangers, these profoundly religious people did not hesitate or delay their democracy until better, more stable times, but plunged ahead with their brave new experiment of one man, one vote - to take place in an entirely religious context - “for the Glory of God,” declares the Compact, “and advancement of the Christian Faith.”

The Pilgrims created their own council, an executive and judicial body, and formed a citizen’s militia. “From the very beginning,” Stanton observes, “all important positions were elective,” including the militia.

While some may scoff at comparisons between the smattering of Pilgrims and multitudinous Iraqis, their commonalities, although removed in time, are nonetheless striking. To paraphrase Stratton, just as the Iraqis are “much poorer than we (in the West) are in material things,” they, like the Pilgrims, are nevertheless “modern people, much closer to us in mind than to those who lived before them in medieval or ancient times.”

Iraqis are extraordinarily well educated and well informed, despite Saddam’s generational tyranny. And their greatest asset may be the thing we most fear - the undeniable power of their religion, Islam, to motivate community formation. For Islam to develop democracy in Iraq, the West in general and the USA in particular needs to look at the regenerative, redeeming powers that can be harnessed from religion, and become more attuned to our own fundamentalist American history.

Having relied on Islam for 1,400 years, Iraqis have a right to demand that its precepts are included in any new constitution.

One of the fears hindering elective democracy in Iraq is that an Islamic government will establish Shariah as the law of the land. But are Shariah courts inimical to the development of democracy? Not necessarily. If history is a guide to evolution, in some aspects, they may even be necessary. Early American law in Plymouth was undeniably fundamentally religious.

Of course, things did not remain this way in the USA and the reasons for such changes are complex. But the recent history of many Muslim states indicates that the Shariah is easily subjected to modernist interpretations, and indeed, was meant divinely to endure and to be constantly reinterpreted to guide new generations.

Could a Shiite government protect other religious denominations, or Islamic minorities? Yes again, if history is any guide. The Pilgrims endured similar religious strife between radical Protestant religious groups - Puritans, Separatists, Anabaptists, Quakers, and general schismatics. Could a Shiite government safeguard minorities? They could, and perhaps even do a better job than early American democrats. That America’s famous reputation for tolerance took several hundred years to evolve seems totally lost on present-day politicians.

What made the Pilgrims’ democracy unique and so enduring was that, from the beginning, these religious survivors could see to that which was beyond any individual and transcended the state, a concept with which they were well familiar. If every voting Iraqi could pledge such similar allegiance to their own individual communities rather than the narrower and more divisive focus of individual tribes, emergence of a genuine Iraqi democracy, even in the form of a religious state, could not only be eventually guaranteed, but preserved.

Given the high literacy and education of many Iraqis compared to other Western democracies, and the traditional loyalty of Iraqis to the smaller community rather than to the larger state, perhaps this end, and not the outside-driven, artificial creation of a wholly secularized modern state, is what the USA and U.N. should work to evolve.

Sarah Whalen is an expert in Islamic law and teaches law at Loyola University School of Law in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

Article courtesy of Arab News