Andrew Lichterman

For a long-time U.S. peace activist, a first visit to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum is both momentous and paradoxical. Much that might move or shock a casual American visitor already is familiar, from the terrible images of human suffering to the facts and figures about the enormous arsenals of weapons of mass destruction still held by the world’s nuclear powers. But there also is much which remains unknown, and perhaps unknowable, about the horror of the use of an atomic bomb against a city, about the annihilation of a community and its people in an instant, leaving behind a sea of ashes amidst a wider circle of suffering survivors and damaged nature.

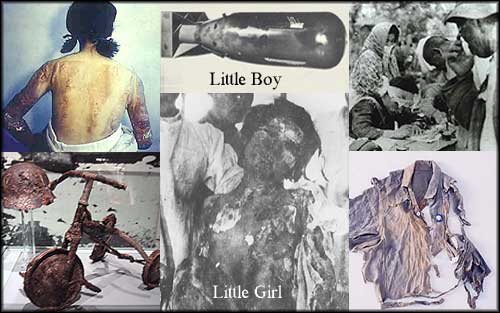

A few images from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

Turning a corner in the Hiroshima Museum, I was confronted by a series of large photographs taken from a perspective seldom seen in the United States. In the country that dropped the bomb, the most common views of the Hiroshima holocaust are of the mushroom cloud, viewed from above and from a safe distance. These photos were taken from near the blast center, perhaps as close as a human being with a camera could have been and have survived. They show the mushroom cloud from below, blocking out the sky above the conflagration consuming the city’s remains.

I made my visit to the Museum just before attending an arms control and disarmament conference. As I sat listening to the speakers, most of them professionals in the field, I felt a long-familiar frustration with the dry logic and sanitizing language of force and counter-force, of “deterrence,” preemption, and the abstract focus on the contending interests of nation-states. Most of the presenters were people strongly committed to disarmament, but for a variety of reasons they had come over time to speak the language of arms control and to channel their energies into its forums and institutions.

Stripped to the essentials, arms control is the view from the plane: it is about where, when, and how to use the bomb. Disarmament, in contrast, is the view from the ground: it is about how to keep the bomb from being dropped on you or anyone else–and how to get rid of it forever. One would hope the latter would have at least equal status with the former, since in the age of nuclear weapons, we all are potential victims. But in most “arms control and disarmament” contexts, it is the language and assumptions of arms control which prevail.

Most intellectual disciplines view the world from the perspective of those who seek to wield power to control both nature and society. This prevailing viewpoint is far more powerful than the intentions of any individual professional or “expert.” It is inherent in the structure of the disciplines: what is considered important to think about, what questions can and cannot be asked. There are many disciplines designed to inform the various tasks of deploying state and corporate power, from law and criminology to public relations, finance and management to the many forms of engineering to the military sciences and arms control. There are few disciplines designed to inform (or even to make visible) the experience of those who are the objects of state and private power: those who are sold to, taxed, propagandized, managed, disciplined, displaced, punished, tortured, and, if those in command find it necessary, annihilated. This too is no mystery. For bank robbers, banks are where the money is. For knowledge workers, the money is in the huge, increasingly interpenetrated organizations of private capital and the state.

And so it goes on. Endless conferences are held, papers presented, grants applied for and received, careers begun and retired from in the disciplines of arms control and “national security,” now with histories, traditions, institutions, and material interests of their own. At the end of every process that begins within this world, the rationalized needs of one or another State, and of all states and the elites which control them, triumph over the clear existential demands of every human individual: to no longer live each day under the threat of extermination. For those on the inside, removing this threat simply is not important enough to step outside the comfortable business-as-usual of this, or any other, set of organizations that dominate modern life.

The extreme example of nuclear weapons only exposes the irrationality of the whole. We all must breath this planet’s air, drink its water, and walk the streets of cities where the violence of poverty and oppression may at any moment evoke a violent response. We will begin to make progress towards the elimination of nuclear weapons–and of the other socially-created dangers that threaten our future--only when our societies shift their priorities towards new kinds of disciplines and institutions, shaped by new kinds of thinking. These new ways of thinking must be grounded in the perspective of those who are looking up at power, up at the planes, up at the mushroom cloud.