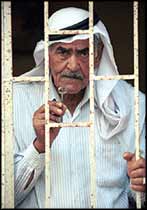

George Bisharat

Last May 14th, the 55th anniversary of the Palestinian Nakba (Catastrophe), when one people gained a homeland and another lost theirs, I was thinking of a home in Jerusalem. It was the residence occupied by Golda Meir, author of the famous remark that “the Palestinian people do not exist” when she was Israel’s foreign minister. It was also the family home built in 1926 by my grandfather, Hanna Ibrahim Bisharat, “Papa” to all of us.

I went to visit our home for the first time in 1977. Although he was a Christian, Papa named the home “Villa Harun ar-Rashid,” in honor of the Muslim Abbasid caliph, renowned for his eloquence, passion for learning and generosity. Painted tiles with this name were inset above the second-floor balcony and over a side entrance.

When Papa first built the home in what became known as the Talbieh quarter of Jerusalem, few other residences existed nearby. As I grew up, my father regaled me with tales of his boyhood exploits in the surrounding field and orchards. Two of my uncles were born while the family lived there; one succumbed to pneumonia in Villa Harun ar-Rashid. The young boys went to school up the road at the Catholic-run Terra Sancta College. My uncle Emile told me of a wager he made with his younger brother, George (for whom I am named), that he could not stand on a swing on the front porch and swing with no hands - with predictable, but fortunately mild, consequences.

The wall enclosing the front yard was a fledgling design effort by my father’s twin, Victor, later a successful architect in the United States, whose buildings helped galvanize the urban renewal of Stamford, Connecticut. My grandparents eventually suffered a reversal of fortunes, and in the early 1930s, leased the house to officers of the British Royal Air Force, expecting to return in better times. Frescoes on the interior walls were plastered over to accommodate the tastes of British officers. My family moved a short distance away to a more modest house on Bethlehem Road. Little did anyone appreciate at the time that the move signified the family’s final departure from Villa Harun ar-Rashid.

A sense of foreboding gripped many Palestinians in the years leading up to the war in the region. Under the gathering clouds of unrest, my father and uncles came to the United States to pursue their higher education, while Papa shifted his business to Cairo. Thus, the family was outside of Palestine on May 14th, 1948, when Israel declared independence and the war with the Arab states commenced. Our fortunes were better than most of 750,000 other Palestinians who were driven out or fled their homes in terror during the fighting.

Villa Harun ar-Rashid was picked by armed Zionist groups for the commanding view it offered from its roof. No blood was shed in taking it, as the British officers simply handed over the keys to the Haganah (pre-state Jewish militia). Like most Palestinian families, we were subsequently stripped of the title to our home through a law passed by the new state of Israel called the Absentee Property Law.

Flooded With Emotion

Villa Harun ar-Rashid was divided into several flats. During the 1960s, Golda Meir occupied the upper flat. Anticipating a visit from then UN secretary general Dag Hammerskjold, it is said, she ordered the sandblasting of the tiles in the front of the house to obliterate the name “Villa Harun ar-Rashid” and thereby conceal the fact that she was living in an Arab home.

George Bisharat can trace his family history in the city back to the time of the crusades. Most ‘Israelis’ are 20th century immigrants or their descendants.

When I went to Jerusalem in 1977, I had only a photograph of the home and a general description of its location from my grandmother. It was summer, hot and dusty, and I paced back and forth through the neighborhood inspecting each of the houses, occasionally asking for directions. All the street names had been changed to those of Zionist leaders and figures from Jewish history, and the hospital that my grandmother had described as a landmark apparently no longer existed.

As I was resting against a wall in the shade, I saw a home that resembled Papa’s. As I hurried across the street, I could just make out the name in the title: Villa Harun ar-Rashid. I guess Golda’s sandblasters had been a little rushed.

I was immediately flooded with emotions - anger, sadness and most of all tension, tinged with fear. I walked through the garden toward the front staircase, putting my hand on the stone banister, as I knew Papa and my own father must have done countless times. I rang the bell.

After a long wait, an elderly woman opened the door. I explained my visit by saying that my grandfather had built the home. I displayed my American passport and asked if I could briefly see the interior. Virtually her first words were: “The family (meaning my family) never lived here.” Later I would understand this as part of the way of rationalizing the seizure of our property: It’s easier to swallow, in moral terms, the expropriation of a speculative business investment by some rich absentee landlord than to contemplate the taking of a family’s home.

At the time I was speechless, as I had never had to confront this claim. When I recovered my wits, I was tempted to apprise her of the truth. But I feared she would deny my entry. The humiliation of having to plead to enter my family’s home with this woman from I know not where in Eastern Europe, perhaps burned inside me.

We were soon joined by her husband, now-retired Justice Zvi Berenson of the Israeli Supreme Court, one of the drafters of Israel’s Declaration of Independence. He permitted me to enter the foyer but no further, saying there was no need to see any more of the house as it had all been changed anyway. The couple insisted that the house had been in terrible repair, and that they had done much to fix it up, a claim I had no reason to doubt. Some 10,000 Arab homes in West Jerusalem were looted and seized in the months preceding the war between Israel and the Arab states in 1948.

Justice Berenson told me that he found the ceilings walls stained with soot - a memento, perhaps, of the Haganah troops’ cooking fires. Yet this narrative of renovation also embodied an urban and smaller-scale version of the myth stating that the Zionists had encountered a barren wasteland and “made the desert bloom.” I later learned, via the research of an Israeli friend and colleague, that Justice Berenson had upheld laws facilitating Israel’s acquisition of Palestinian lands through what amounted to legalized theft.

Imagining Voices

The house was cold inside, and as I stood there, I tried to imagine the sounds of my father’s and his siblings’ voices, and the smells of grandmother’s cooking. I left after no more than five minutes. Walking back out into the blazing sun, I felt no specific hostility toward the old man and woman living in Papa’s home. But hospitality, such a strongly held value in Palestinian culture, is hard to uphold when guests become usurpers.

In 2000, we made this same pilgrimage as a family. As we stood across the street, I recounted the story of Golda Meir’s defacement of the title to my son and daughter. I was overcome. Instantly my little son embraced my leg, then my daughter huddled my waist, and finally my wife my upper body, and briefly we stood there, hugged together, tears streaking all our faces. Shortly, we composed ourselves, crossed the street and wound through the garden to the front steps.

The front door swung open and a man smilingly offered: “May I help you?” Somewhat startled, I thanked him for his kindness, and he explained: “Many tourists come to see this house. It’s included in walking tours of the city.” The man, an American from New York, permitted us to enter and venture through more of the first floor than I had seen before. But when I said that my father’s family had lived in the home, he was incredulous. This time, I was not surprised as he protested, still congenially: “But the family never lived here.” He had gleaned this from a newspaper article, he maintained. Repeatedly, he insisted, it seemed a half-dozen times: “The family never lived here.”

Of course, the family did live there, notwithstanding the denials, justifications and obfuscation we have faced. Likewise did hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians “live there.” The keys to their homes there still adorn the walls of apartments, houses, rooms and refugee hovels throughout the world.

We have not disappeared, nor have we forgotten - our existence a reminder that one people’s liberation was founded on another’s dispossession. At home in California I have a thick file containing the documentary record of my family’s effort to regain Villa Harun ar-Rashid. We have not prevailed, of course, nor have we ever received any acknowledgment of the injustice we, and countless others, have suffered. Our homes and properties were long ago transferred to the ownership of the state or quasi-governmental agencies that, even today, do not lease or sell land to non-Jews.

Recently I found my daughter lingering over photos of my father as a boy in his Jerusalem home. I know now that she and my son both are heirs of the truth about Villa Harun ar-Rashid.

Professor George Bisharat teaches at the University of California’s Hastings College of Law in San Francisco

Article courtesy of Haaretz