Kirsten Zaat

When I was 16 I was sent to Egypt to ‘spread peace and inter-cultural understanding’ as a corporate youth ambassador for Australia. That opportunity opened my eyes and my heart to Arabs and Muslims and changed my life forever. I returned to high school in Australia and began studying Arabic at Saturday school. I then studied Arab and Islamic culture, Arabic, political science and law at university. I have worked for a number of international aid agencies since, including CARE International and the United Nations in Egypt, Cyprus, Jordan, Southern Lebanon, Occupied Palestinian Territory and Iraq.

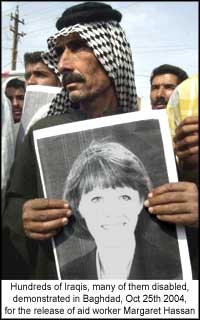

Most recently I was the Head of Office for the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) in Kuwait, facilitating cross-border humanitarian assistance into Southern Iraq. I have been living and working in the Middle East intermittedly now for more than 15 years. When I began my career, Margaret Hassan had already been living in Baghdad for 15 years.

I first met Margaret in her role as one of the Executive Board members of the NGO Coordinating Committee for Iraq. I was the UN’s NGO Liaison officer for Iraq, nominated by the global NGO community. We would meet every Tuesday at UN headquarters in Baghdad with the UN Humanitarian Coordinator and other NGO representatives to discuss the humanitarian issues of the moment. The discussions were frank and the humanitarian issues were many.

I first met Margaret in her role as one of the Executive Board members of the NGO Coordinating Committee for Iraq. I was the UN’s NGO Liaison officer for Iraq, nominated by the global NGO community. We would meet every Tuesday at UN headquarters in Baghdad with the UN Humanitarian Coordinator and other NGO representatives to discuss the humanitarian issues of the moment. The discussions were frank and the humanitarian issues were many.

UN sanctions had precipitated a 13 year long humanitarian crisis for the people of Iraq and Margaret had worked tirelessly for CARE since 1991 in the interests of guaranteeing Iraqis their basic human rights, including access to clean drinking water, sanitation and health care. Margaret and I shared a profound concern over the US-led invasion of Iraq. We knew the insecurity such an attack would unleash would further prevent humanitarian access to those same communities that had been laboring under the brutality of the sanctions regime.

We knew the war on Iraq was and is based on shortsighted, unilateral design that is ideologically driven and privies economic and other national interests over good global citizenship, social justice and human rights. As long-time students of Middle East politics, we also feared the unraveling of Iraqi society, the further destabilization of the region, and the irreparable damage the war would do to East-West relations.

As the invasion progressed, Margaret and I both became gravely concerned by the blurring of civil-military distinction in Iraq - the involvement of the US and UK military in the delivery of humanitarian assistance and the implications this had for the security of Iraqi communities and aid workers alike. Perhaps this is why she, like so many of us, remained considerably frustrated by the inability of the US and UK Government to provide the security in Iraq that we needed as humanitarians to get the job done.

In an environment framed by military curfews and an 8pm lock down, Margaret resented having to spend so much time advocating on the obligation of the Occupying Powers to take up their law and order responsibilities in accordance with international humanitarian law. She also resented the dangers the lack of security presented to her staff and the ever-growing inability of humanitarian workers to reach communities most in need.

Along with our Oxfam colleagues, it was our firm belief that the more humanitarian space was eroded in Iraq, that is, the more the military delivered aid in order to win hearts and minds; the more NGOs were forced to act as instruments of foreign policy; and the closer the humanitarian community naively became to the Occupying Powers in the interests of better coordinating responses to Iraqi need, the greater the risk posed.

The blurring of civil-military distinction and the resultant death of humanitarian space in Iraq culminated in the bombing of my office (UN Headquarters) in August 2003 and ICRC headquarters in October 2003 killing 26 humanitarians and injuring almost 500 others. The demise we sustained as an aid community was overwhelming. We lost good friends and the world lost great humanitarians. Margaret’s capture is yet another consequence of the death of humanitarian space in Iraq.

Given Margaret’s heart wrenching plea for help on Friday (October 22 2004) it would appear that it is the Mujahideen that has captured her. And to every Jihadi involved I say uncompromisingly - Margaret is acting on no-ones behalf other than the people of Iraq. She is not an emissary, she is not a collaborator, and she is not a combatant. This is not a woman who represents the unjust agendas of the Bush, Blair or Howard Administrations.

Margaret has dedicated her life to helping the international community understand that there is no ‘clash of civilisations’. Rather there is only ‘we the peoples’ who are entitled to enjoy our rights while fulfilling our universal responsibilities to protect our fellow human beings. ‘We the peoples’, whether in Iraq or Australia, are simply trying to go about our daily lives - working, discovering love, getting married, having healthy children, and finding solace and enjoyment in family and friends.

The last 15 years have taught me that ‘we the peoples’ have more in common than we differ. And Margaret has spent more than 30 years now trying to convince the international community of this while tirelessly working to ensure that all peoples enjoy their rights and uphold their responsibilities in dignity and in hope. I hope whoever has taken Margaret away from us realises the momentous mistake they have made and shows the generosity and compassion to right their terrible wrong.

Margaret is a woman, a community elder, and a humanitarian aid worker. She is protected under both international humanitarian law and the Shari’ah. As the Sunnah teaches us (Sahih Al-Muslim, Kitab al-Birr, Narrated by Abu Huraira, 59), the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, himself privileged humanitarians: “[W]hosoever removes a worldly grief from a believer, God will remove from him one of the grieves of the Day of Judgment. Whosoever alleviates a needy person, God will alleviate from him in this world and the next”.

Having wrongly abducted Margaret from the Iraqi battlefield as a prisoner of war, according to The Holy Qur’an (Chapter 47:4), her captors now have two choices - either show generosity and grant her freedom, or take a ransom and release her. These are the only options ordained under Islamic Law. Either way, Margaret must be set free.