Jeff Riedel

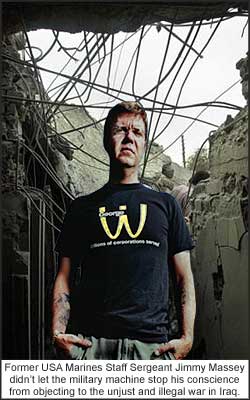

Former Staff Sergeant Jimmy Massey, a 12-year Marine veteran, lives in Waynesville, North Carolina, a small town in the Smoky Mountains just outside of Ashville, where he spoke to the World Socialist Web Site. He is one of a growing number of American soldiers returning from Iraq who have become outspoken opponents of the war.

Massey entered Iraq as part of the initial US invasion in March 2003. He witnessed—and in some cases participated in—the killing of innocent civilians. During a single 48-hour period, he says, he saw as many as 30 civilians killed by US gunfire at highway checkpoints.

The brutality of the US military’s retaliation against the growing resistance of the Iraqi people transformed his view of the occupation and changed him for life. Massey, horrified and unable to reconcile himself to what was taking place, began to speak out to his superiors. He was eventually medi-vaced out of Iraq and diagnosed with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Labeled as a conscientious objector by his commanders, Massey sought legal counsel and won his honorable discharge in December 2003.

Massey grew up in the mountains of western North Carolina. His father was a truck driver who was shot and killed during a confrontation with the Florida State Police when Massey was still in his early teens. He then moved with his mother to Texas, where she took a job with the Texas Board of Corrections. He grew up in a household where at times there was very little money and little to eat. He would eventually join the Marines and became a recruiter himself in the late 1990s. He was sent to Kuwait in December 2002, in preparation for the invasion of Iraq.

Massey’s disillusionment with the military began as a recruiter, when he started to question the methods used by the Marines in preying on young people from economically depressed areas. His feelings would soon be deepened by his experience in Iraq.

Massey’s disillusionment with the military began as a recruiter, when he started to question the methods used by the Marines in preying on young people from economically depressed areas. His feelings would soon be deepened by his experience in Iraq.

“You know, these kids are just thankful that they’ve got some health care—for a lot of them, the first time they even went to the dentist is when they joined the Marine Corps. Then you pump them full of patriotism and intangible benefits—self-confidence and what not—and now you’re indoctrinating a young person with an ideology.

“Boot camp is designed to dehumanize and desensitize a person to violence. I was a Marine Corps boot camp instructor for two-and-a-half years, and I know that it is designed to strip you down and rebuild you. The only purpose of the Marine Corps is to meet the enemy on the battlefield and destroy them.”

Massey asserted that, given the economic conditions in the US today, there exists what amounts to an economic draft of young Americans into the military.

“A large percentage of the so-called growth in this country is associated with the military. The bottom line is, for the Halliburtons and Enrons war is good, but for the poor and for all of the soldiers coming home, especially the ones coming home wounded, there’s not much of a future. But for a lot of the kids getting ready to graduate high-school, the military is looking pretty good because their families have no money to send them to college.”

Massey’s career as a recruiter ended after he wrote a mission statement to his commanding officers, outlining his personal concerns with the issues of recruitment. The process of reaching the point of speaking out was not an easy one, he recalled.

“It’s very hard to break away from—you have to reach down deep in your soul for answers to questions that begin to come up. And what happened with me was, I was coming into contact with groups like the War Resisters League while I was out on recruitment duty. They were out there counter-recruiting. I started reading some of the literature that they were passing out at the high schools. I became curious and started doing my own research, finding out certain things about America’s involvement in other countries.”

In Iraq, Massey was brought face to face with this involvement. The initial invasion took on the character of a one-sided slaughter, with the world’s strongest military power armed with the most technologically advanced weapons, on the one hand, and a disarmed and virtually defenseless military of a country already devastated by a decade of sanctions, on the other.

“We were like a bunch of cowboys who rode into town shooting up the place. I saw charred bodies in vehicles that were clearly not military vehicles. I saw people dead on the side of the road in civilian clothes. As a matter of fact, I only remember seeing a couple of bodies in military uniform the whole time.

“There wasn’t a whole lot of direct fighting to speak of. There were some firefights—I mean I had bullet holes in the side of my Humvee—but it wasn’t like major combat action. We took the highway the whole way up to Baghdad. They had no artillery; they had no air support. They were so weakened by all the sanctions. All of their equipment was in very bad shape. Most of their hardware was left over from the war against Iran. The first Gulf War just devastated them. I don’t think they had the will or the opportunity to fight.”

Massey said that the hostility of the Iraqi people to the presence of the US military grew exponentially over the time he was there in direct response to the brutal methods employed by American troops against the entire Iraqi population.

Massey manned a number of US military checkpoints on Iraqi highways in the months following the invasion. He described how, when cars failed to stop, out of confusion or otherwise, the order was to ‘light them up’ or open fire. It was at one of the checkpoints that Massey’s attitude toward the war reached its turning point.

Massey described the chaotic and reckless character of the roadside checkpoints and the indifference of the military leadership to the culture of the people that they were there supposedly to help.

“The bottom line is they [the military command] don’t see the need to teach culture and humanity to men whose singular purpose is to kill. And that was just one of the cultural mis-cues. I blame the top of the chain of command, from the President down to Tommy Franks [the former commander-in-chief of US occupation forces] to General [James] Mattis [commander of the First Marine Division]. They all knew that the military was not trained properly when it comes to dealing with Muslim culture and a foreign land. But that was not our purpose for being there.”

In the midst of the widespread killing of civilians, Massey was struck by the callousness of the military command and the lack of humanitarian assistance they were offering the Iraqi people. This further deepened his doubts about the true purpose of the war.

“But I’ll give you an example of what we actually did. After we shot up this car with civilians, I called in the corpsmen to bring in stretchers. They came in and put two men on stretchers. Five minutes later, they brought them back and dumped their bodies on the side of the road. They were still alive. They were riddled with bullets—one guy was just rolling in agony on the side of the road.”

At the time, intelligence reports were streaming in describing insurgents and rebels driving ambulances and civilian cars. In a growing atmosphere of fear within US military ranks, the entire Iraqi population was now viewed as the enemy.

A recent study estimated the number of Iraqi deaths since the start of the war in March 2003 at around 100,000. When asked if this number seemed accurate, Massey responded:

It is now well established that all of the pretexts for launching the unprovoked war in Iraq were based on manipulated intelligence and lies. In its drive toward war, the Bush administration fraudulently exploited the September 11 attacks to spread fear and panic throughout the country, and this, as Massey notes, was very effective in the South, where he is from.

“He used this influence in part to sell the war in Iraq, based on fear. But the tide is turning. I think a lot of Southerners are saying ‘enough is enough - it’s time to get out of Iraq.’ I just read a letter to the editor in the Mountaineer, a small local newspaper down here. The lead article on the front page is about a high school football game—I mean this is a small-town paper. The letter is called ‘Country needs to get out of Iraq’ and here’s what it says:

“‘Hindsight is 20/20 and this is a war that should have never been fought. As a Navy veteran with more than 20 years of service, I would be the first one to step forward in the defense of our country. This is not the case here—President Bush has a personal agenda. Arab oil is not worth any American life. We need to get our troops home now! Let’s redirect our talents and energies to finding alternate energy sources.’”

Diagnosed with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, Massey was sent home to argue his case against a dishonorable discharge in the summer of 2003.

“I had a seat in his office, and he said that the Sergeant Major over in Iraq had sent him an e-mail explaining everything, and that I should stop worrying, that he was going to fix everything and it would all be okay. But just before I started to speak, I saw him reach into his desk drawer and pressed what I know was the record button on a tape recorder, and then he closed the drawer really fast and acted all nonchalant. I was thinking, ‘Damn, if you’re going to entrap me then at least try to cover it up a little.’

“So I sat there saying nothing, and finally he says, ‘You know, you only have another seven years to retire—we’re going to move you to a nice little office somewhere or passing out basketballs or something like that...you’ve got a lot vested in the Marine Corps and you need to think about your retirement.’

“I stood up and said ‘Well, Sergeant Major, I don’t want your retirement and I don’t want your benefits. We killed innocent civilians, and you have to face that responsibility, and I’m going to tell everybody what happened.’ I remember his face turned red, and he said that there was going to be legal repercussions that go along with that decision. I told him that I would not expect anything less from the Marine Corps.”

Massey recalls walking directly from the meeting to the Base Exchange, where he picked up a copy of the Marine Corps Times and called a lawyer who was listed in the back. The lawyer was Gary Meyers, whose practice dates back to the My Lai trials during the Vietnam War. There was no trial for Massey. In the end, the Marines backed down and agreed to his honorable discharge. He is currently working on a book and plans on using whatever proceeds there are from it to start a post-traumatic stress disorder foundation.