Gabriel Ash

Just as the world learned about the secret Geneva Accord, supposedly a groundbreaking blueprint for a comprehensive peace between Israel and a future Palestinian state, the parents of two Palestinian children in Rafah learned of their children’s death at the hands of brave Israeli pilots. Hence, the accord, even before anyone read it, had already helped the Israeli “peace camp” fulfil its traditional diplomatic role, deflecting international attention from the horrible things Israel does, to the pious chants that accompany expressions of Israeli hopes for peace.

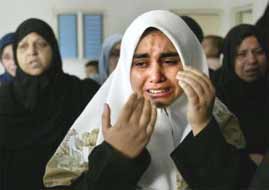

The sister of Palestinian teenager Zaki Alshareef, weeps during his funeral, after he was killed when Israeli forces razed scores of homes in the Rafah refugee camp.

The driving personality behind the Geneva Accord, the indefatigable Yossi Beilin, has already brokered a number of “peace” blueprints. In theory they all call for a Palestinian state alongside Israel, the so-called “Two State Solution.” In practice their mathematics of Palestinian statehood are more fractional. The “Oslo Accord,” with its almost total absence of Israeli obligations, should probably be called the “1.2 State Solution,” whereas at Taba in 2000 Beilin went all the way up to a “1.4 State Solution.” A full and free Palestinian state has never been on the table.

Not satisfied with the results, Beilin recruited another team of negotiators, found a willing Palestinian partner in the team led by Yasser Abd-Rabbo, and produced yet another blueprint. But does it go beyond the fractional? Does it recognize Palestinians as equals? Or is it more of the same, at best a “1.5 State Solution”?

The Geneva Accord does show measured progress in Beilin’s willingness to accept Palestinians as equals. It gives up the Israeli demand for control over the Al Aqsa Mosque. The borders between Israel and the proposed state are closer to the Green Line than in any previous map. Land swaps for border settlements are to follow a 1:1 area ratio, significantly better than the 1:10 proposed by Barak at Camp David, though still falling short of any real equality; Palestinians are to give away some of the best land they have for stretches of desert.

But reading the document as an agreement between Israelis and Palestinians misses the point. The Israeli drafters had no authority to negotiate, and no Israeli government is going to sign such an agreement in the foreseeable future. The Palestinian team represented an unpopular Quisling leadership engaged in a last ditch effort to maintain power. Rather, the Geneva Accord is a political marketing plan for the mutual revival of the oxymoronic “Zionist Left” and its Palestinian counterpart, the PA. It is most illuminating as an illustration of the crippled vision of that ideology. Since marketing is more about dreams than details, we can learn more by looking at the spirit of the document than by a point-by-point analysis of what the accord has to offer each side.

One starts by noting how verbose the accord is. There are details upon details, competing with each other in their insignificance. For example, clause 10.3; “the parties shall agree on requirements and procedures for granting licenses to authorized shuttle operators.” No kidding! As if the hundred year war in Palestine was really a bureaucratic scuffle over taxi medallions. Obviously, unauthorized shuttle operators are out of luck. But more importantly, the clause, in addition to dabbling in trifles, says nothing at all about its superfluous subject. It merely commits the signatories to more talks. To those who remember Oslo, it should be deja vu all over again.

Yossi Beilin and Yassir Abed Rabbo, with their reliance on euphemisms, platitudes, and multi-clause non-commitments, may make good careers in politics, but they will never achieve peace for Israelis without justice for Palestinians.

The accord is full of such content-free clauses, as well as clauses evoking future agreements that haven’t been made yet, and clauses referring to not yet written documents. Annex X, which doesn’t yet exist, is referred to no less than fifty-two times. Annex X is supposed to define major questions, for example, the right of Israel to access roads in the Palestinian state. Suffice therefore to say that the accord makes a strong effort to hide beneath the verbiage the fact that crucial issues defining the extent of Palestinian independence are left unspecified. It thus reveals yet again that the “Zionist Left” is constitutionally unable to accept Palestinian sovereignty on equal footing.

Most telling is Article 12: “Water—still to be completed.” Water is not a trifling matter. It is one of the most important issues requiring resolution. Given that the drafting of the Geneva Accord took many months, one is left to wonder why time wasn’t found to define the way Israel and the future Palestinian state will share their common water system, when more than enough time was found for arguing about licensing buses. If the drafters were really interested in a “just peace,” as they claim in the preamble, Article 12 could have been very short indeed, say “access to the water resources of Israel and Palestine will be distributed between them in proportion to the size of their population.” That is clearly the only just way to distribute water. If there is any difficulty in the issue, it resides in the fact that right now Israel takes most of the water, leaving Palestinians with an average consumption as low as one third to one ninth of the average per capita consumption in Israel. In many places Palestinian have only half of the amount of water considered the necessary minimum by the World Health Organizations, while nearby settlements irrigate lush gardens and grow water-intensive cotton with subsidized water. It is clear from the silence of Article 12 that Beilin and his team, even when they write a symbolic text supposedly expressing the hopes of the Israeli “peace camp,” are not ready to put an end to this discrimination.

The accord is marbled with the arteries of colonial thought processes. For example, even before a Palestinian state is created, it is obliged to cooperate with Israel on areas of culture, sports, science, etc.; practically—on everything (clause 2.8), as a condition for its existence. Perhaps Palestinians can benefit from such cooperation, but it didn’t occur to the drafters that the citizens of the new Palestinian state might have the right to decide if and how much they care for the bosom friendship of their former oppressors.

Something deeper is at stake. Beilin’s new agreement commits Palestinians to what in Israel is called “a warm peace.” The “Zionist Left” was deeply disappointed by the way peace with Egypt turned out to be “cold,” namely peace with the authoritarian government of Egypt but not with the people of Egypt. This time, Beilin’s marketing ploy promises Israelis, peace will be warm. Palestinians will not only stop blowing up buses. They will actually embrace Israelis and do joint theatre productions with them. This absurd yearning to be loved by Palestinians is rooted in the correct understanding that only Palestinians can confer legitimacy on the state of Israel. The forced transfer of property from Palestinians to Israelis (in other words, the grand land robbery) cannot become a legitimate transaction without a Palestinian seal of approval, which Arafat and his cronies are eager to grant for nothing but their power in exchange.

It is not that reconciliation is impossible. Forgiving may be divine, but people have often found the strength to forgive the worst abuses. The absurdity of the Zionist Left peace fantasies resides in the fact that it wants the slate to be wiped clean without ever taking responsibility for Israel’s actions; indeed, it wants to be forgiven while the crime goes on!

This is clearest in the way the Geneva Accord handles the refugee problem, because the refugees are at the heart of the Palestinian national trauma.

Beilin’s triumph, in terms of Israeli politics, is that he got the Palestinian team to accept a “solution” to the refugee problem in which the right of return is not recognized. A few refugees might be allowed back into Israel. But, according to the agreement, Israel’s contribution to the resettlement of refugees would be based on the principle that Israel is merely one of many countries participating in a purely humanitarian effort. As part of that international effort, Israel would accept, at its own discretion, at best an “average” number of refugees. This is deep denial, for Israel’s responsibility for creating the refugee problem is both a historical fact and a legal one, repeatedly reaffirmed by the U.N. It is particularly ironic that those who have worked hardest to turn denial of responsibility into a crime in itself (see “holocaust denial") are deepest in denial about their own responsibility.

The preamble of the Geneva Accord affirms Israel’s desire for a “just peace.” This is welcomed. But unfortunately, nowhere in the text, certainly not in the chapter on refugees, can one find a statement about what past injustices need to be righted. Beilin’s “just peace” is a lot like Sharon’s “painful concessions,” a vague statement of principle without application. The “Zionist Left” believes in a just peace as long as nobody mentions the injustices that a just peace ought to rectify.

This is therefore the colonial paradox at the heart of the Geneva Accord. On the one hand, the requirement of full reconciliation, friendship and justice, couched in the demand that Palestinians fully accept, indeed love, Israel. On the other hand, the foreclosure of any Israeli recognition and acceptance of the historical tragedy of Palestinians. Nothing conveys the Geneva Accord’s commitment to being deaf and dumb better than Article 5.9(b).1:

“The Israeli Air Force shall be entitled to use the Palestinian sovereign airspace for training purposes in accordance to Annex X...”

Forget sovereignty. Just consider this: the victims of Israeli bombardments, the relatives of the martyrs of Israel’s assassination policy, the parents of the children killed by Israel’s air-to-ground missiles, the refugees who will presumably return to the new state from Lebanon, still carrying the scars, still living the nightmares of Israel’s massive aerial destruction of scores of refugee camps, will forever be able to raise their eyes to the sky, to what would presumably be “their” sky, and see their tormentors fly.

Beilin’s blueprint, even in the extremely unlikely event that it is followed, won’t be the end of resistance, and it won’t be the beginning of peace. Those Israelis who yearn for peace must understand that peace and reconciliation will not happen before Israelis come to terms with their actual history and their national and personal responsibility for the Palestinian tragedy.

Article courtesy of Yellow Times