Mark Mazower

Is anti-Semitism on the rise in Europe? Ariel Sharon, Israel?s Prime Minister, this week gave warning of the re-emergence of “an anti-Semitism that has always existed”. Attacks on Jewish targets in France and the bombing of the two synagogues in Turkey look like straws in the wind. And when a German MP assigns the Jews responsibility for the crimes of Bolshevism and the commander of the German special forces publicly agrees, then it is worthwhile addressing the question.

German MP, Martin Hohmann, was recently expelled from the his party, after claiming that ‘one could describe Jews with some justification as a Taetervolk’ - a ?race of perpetrators? of rights abuses.

No historian would want to deny the extent of European anti-Semitism in the early 20th century. However, the Holocaust led to a profound transformation of attitudes in Europe. After the war the commonly-held belief in scientific racism fell into disrepute and UNESCO issued its famous declaration that race was a social myth. The basic law of Konrad Adenauer?s West Germany explicitly outlawed racial prejudice.

The Holocaust itself has become the single most-studied episode of the war, if not of the 20th century, and today there are Holocaust monuments, memorial days and museums ? even in countries where it did not take place ? and laws which criminalise Holocaust denial. So, contrary to what Sharon has indicated, only a few oddballs regard expressions of anti-Semitism as politically or culturally acceptable.

Over the past 40 years there has been a huge generational shift in attitudes, and even the genteel prejudices of an earlier generation grate on the ears of the young. If a few echoes linger farther east, these too are dying away with the transformation of post-communist societies.

But if the Holocaust eradicated anti-Semitism as a political force in Europe, it had another far-reaching consequence as well: it gave birth to Israel, thereby linking Europe, the Jews and the Arabs in a new way. If Israel looms large in the European political consciousness, it is not because Europeans are anti-Semites but because Europe itself is in many ways the architect of the present imbroglio.

At a time when most Jewish emigrants were heading to the United States, Argentina and Western Europe, the British ? for their own reasons ? gave the green light for the creation of a Jewish national home in an Arab province of the Ottoman Empire. The British, the French, who successfully fought to prevent a Hashemite Greater Syria emerging in 1920, and the Nazis, who drove huge numbers of Jews into Palestine, between them turned out to be indispensable for the success of Jewish nationalism.

Zionism, which brought “the people without land to the land without people”, in fact implied the dispossession of Palestine?s Arabs. Previously, anti-Semitism had been a negligible factor among the Arabs; there was little trace of it in the Ottoman world, where Jews and Muslims coexisted harmoniously.

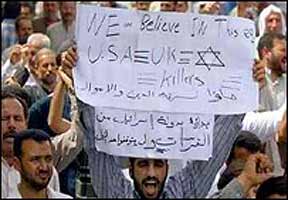

But even as European anti-Semitism dwindled, so it seemed to grow in the Middle East, fed by racial and religious myths imported from the defeated European Right.

What has emerged is not at heart a racial antagonism but a political one ? an anti-Zionism which takes Israeli rhetoric at face value by conflating Israelis and Jews. This is very different from the old inter-war European variety. The Nazis were not much bothered about Jews? political opinions; what counted was race.

The overwhelming majority of Muslim and non-Muslim critics of Israel say that it is not Judaism or Jews that they hate, but the racist ideology of Zionism and the excesses of Zionists

If anything, Zionists were the one kind of Jew that right-wing Europeans were prepared to deal with, since both sides desired the same thing ? the departure of the Jews from Europe. Precisely the opposite is true for Arab opinion: conspiracy theories flourish, and so does Holocaust denial, but the real target is Zionism as a political doctrine.

Israeli spokesmen, however, are now focusing not on sentiment in the Arab world but on signs of old hatreds in Europe. By doing so, they badly distort what is happening. When a German MP is forced to resign after comparing the Nazis with Jewish Bolsheviks, we are learning more about German frustrations over how the world deals with the Holocaust than about the dangers facing German Jews.

Recently there has been a remarkable increase in the number of Israelis settling in Germany: so much for anti-Semitism there. Neo-Nazi and far-right groups continue to target synagogues and cemeteries. But this has been going on for years and has not pushed them into the mainstream ? quite the contrary.

What is new in the present equation is the violence mostly in France by young Arab youths against Jewish targets, a spill-over into Europe of the kind of anti-Zionism already described.

Before we turn to the old catch-all labels of the past, we need to take a good look at the singer as well as the song. “The best solution to anti-Semitism,” Sharon said in Rome last week, “is immigration to Israel.”

As Jewish migration from the former Soviet Union dwindles, the spectre of depopulation looms large among Israeli officials who fear Jews may before long be outnumbered by the fecund Arabs in their midst. Sharon is the man, after all, who entered office vowing to bring a million new settlers to the country in order to reverse its alarming demographic deficit.

There has always been a debate among Jews about the importance of anti-Semitism in Europe, and Zionists for obvious reasons have tended to emphasise the threat it poses. But today Israel itself looks more like a source of danger for Jews worldwide than a refuge, and even Israelis ? though the emigration statistics remain a closely guarded official secret ? are voting with their feet.

If Sharon is seriously concerned about anti-Semitism, there is no one better placed than he to do something about it by changing his Government?s policies towards the Palestinians.

The author is Professor of History at Birkbeck College, London.

Article courtesy of The Times