Free of Saddam, Jailed by Poverty

Dahr Jamail for the World Crisis Web

I took yesterday ?off? by basically hibernating inside my hotel room. As has happened so often before, I found myself tired and depressed after covering so many different aspects of the occupation-from maimed and dead bodies in hospitals, to one demolished building after another staring me in the face throughout Baghdad, to witnessing grinding poverty, to the constant threat of being blown up by an IED (Improvised Explosive Device) or shot by a trigger happy USA soldier. After awhile it all tends to get a guy a bit down.

I can only imagine how the people of Iraq get by on a daily basis, and continue to push forward with life, having endured years of war, 13 years of devastating sanctions, and now an occupied homeland.

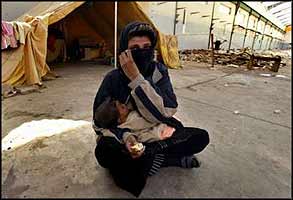

Finding safe and hygienic accommodation is a lottery for Iraqis made homeless by invading forces.

Today I went to the Iraqi Air Defense Ministry. Or more precisely, what?s left of it. For what used to be a proud complex of buildings in central Baghdad which housed generals and airmen from the Iraqi Air Force, is no longer. Bombed during the Anglo-American Invasion, many of the buildings have been reduced to large heaps of broken concrete and metal.

What is left of the other buildings has been looted to the bare walls; even the marble siding has been pillaged. As some journalists and myself walk through the complex towards the back, nothing but garbage, dirt, broken glass, useless scraps of tin and various

sorts of rubble litter the ground all around. Like guts hanging from the ceiling, long pieces of scrap metal swing lifelessly. Whatever they supported or were attached to, has long since been looted. The typical black flame marks are smeared above the outside of the window areas.

Today the Air Defense Ministry serves as a makeshift refuge for people and families with little or no income. Children with dirt smeared into their faces and arms run about the area near two swimming pools, which now are filled with one meter of dark brown scum, littered with garbage floating lifelessly above.

Hussein Khalaf Hussein, a shoeless man with unshaven stubble on his face invites us into a building where several families and men are squatting. Barren rooms serve as homes for people, with only a couple of blankets and a few dishes lying around on the grimy floor. He gives us the quick rundown of how the area is divided into four sections. Each section has a representative who brings and distributes food and supplies (when lucky enough to find some) to families in their section.

Mr. Hussein is a Shia man who fought the Iraqi Intifada which stood up against Saddam Hussein?s regime in 1991 when the Americans asked them to do so, promising support. After the uprising was crushed when the American?s failed to follow through on the promise of supporting it, like so many others Mr. Hussein fled the country for his own survival. He returned from Lebanon two weeks ago.

Homeless Iraqi children use the relative safety of a warehouse, and all of their imagination, to pretend that the world really is a place for them to grow up in.

While we are talking another man tells us that some British army personnel brought them some blankets six weeks ago. As far as the Americans, two months ago some men came by to take photos of everyone in the gutted buildings, but have brought no supplies.

Another man walks up to us and says,

"Saddam is gone, and look at us! We have nothing. No medicine. No food. Living like animals. What have the Americans done for us? The Americans make all these promises, but have done nothing, and they have made everything so expensive."

Mr. Abbas Abu Fadel, is a Shia man who lives in one of the old houses in the complex which used to be inhabited by Ba?athist Generals. Abu Fadel has been here longer than everyone else, having moved in immediately after the invasion of Baghdad and now serves as a representative of one of the sections of this area.

He invites us into his home at the edge of the bombed out complex for tea and to talk with us. As per Arab custom, he is welcoming and pleasant, saying

"Anyone invited into my home is my family and my friend. You are most welcome here."

We sit on the carpet of the scantily furnished room; a lone television sits off to the side on the single piece of furniture-an old cabinet with a few stuffed animals sitting atop it.

He tells us how he escaped from the Iraqi Army in 1989, but was thrown in jail on a regular basis by the Ba?athists for distributing anti-Saddam leaflets. Between his stints in jail he would sneak around to do work as an air conditioner repairman.

A large explosion booms in another part of Baghdad while he talks with us.

“I was poor, and I still am. This is my life. This is the life for all of us here. We are only here because there is nowhere else. My landlord kicked me out of where I was living before because I had no money."

Tanks rumble down the road next to the home he and his family of five are squatting in.

According to Abu Fadel, there are 375 families living in squalor here, and a total of around 4,000 people.

He shows us a stack of forms from the Iraqi Organization for Victims of Terrorism. He says this organization is supported by the USA in order to give compensation for people who suffered under the rule of Saddam Hussein.

“I hand out these forms to all of the people here, and tell them to fill it out and turn it in to try to get some money and food."

Oppressed under Saddam, oppressed under Paul Bremer.

Iraqis have seen this tyranny before.

I ask if anyone has had any success in being compensated by the Americans, via this Iraqi organization.

"All I have gotten has been from NGO?s and rich Iraqi people who donate things for the poor."

He points to the compensation form he is holding in his hand.

“This is nothing. This is only promises."

We ask how he feels about the Americans being in Iraq.

“The Americans are here, but we can?t complain about them occupying our country. They tell us they are here to help us, yet we know they are occupiers. For now there is nothing we can say because they tell us they are here to defend us from the people who support Saddam."

He obviously has mixed feelings about the all powerful military of the USA who effectively removed the nightmare of Saddam Hussein from the lives of the Shia people like himself.

“At first I disagreed that Iraq was occupied. We supported the Americans in getting rid of Saddam. Now I admit we are occupied. My opinion is that I give them another 6 months, maybe 2 years to help us rebuild. I know they came here for the oil though."

Abu Fadel sips some tea and continues.

"I think the USA will take all of the oil. But Saddam also took all of the oil for 35 years, so what is the difference? The oil didn?t help me then, and it doesn?t help me now, so why should I care? Sure it makes me upset, but what can I do about it?"

He is asked what he will do in the future.

“I don?t have the power to stand against the Americans, so I?ll close my mouth and wait. It?s better for me that the nightmare of Saddam is gone. We will follow our leaders. If they say wait, we wait. If they say fight, we fight. Right now we wait. This is my country. I hope George Bush will be honest with us and do as he has promised. I just want a place to live and to not be forgotten. I want to be safe and live a normal life. This is all that I want and need."

He continues,

“I would continue to live here if the American?s rebuild this and let us stay here. Under Saddam I couldn?t dream of this; I have a television, CD player, and carpets."

After our talk, he takes us out to show us more of the compound, of how other families are living. His home is luxurious by comparison. A family of seven has moved into a large public bathroom. Dirty carpets cover the floor, and a shoe-shine box sits near the entryway.

The man living here stands up and apologizes to us for his home.

We walk amongst the rubble under a dreary grey sky to view another bombed out section. While walking Abu Fadel says,

“I think our leaders will call for jihad against the Americans because we are all living in such a terrible situation.”

Published Friday, January 2nd, 2004 - 05:43pm GMT

Dahr Jamail, is an independent journalist from Anchorage, Alaska, living and working in Iraq. He reports regularly for the World Crisis Web. He can be reached at dahrma90@yahoo.com

An original publication for the World Crisis Web.

This is the print-ready version of Free of Saddam, Jailed by Poverty

Dahr Jamail for the World Crisis Web

It was found in the Occupation Woes section of the World Crisis Web.

To view and post your views on the article in full go to http://www.world-crisis.com/analysis_comments/P324_0_15_0/