Shiites Gaining Power In Post-Saddam Iraq

Hamza Hendawi

A 22-year-old Shiite cleric wields vast power in the impoverished Iraqi city of Kut, overseeing a network of social and security services, collecting taxes and even administering a court of law - all independent of the U.S.-backed local government. Abdul Jawad al-Issawi is an example of the eroding influence of the U.S.-led coalition and of how Shiite clerical power is spreading outside the mosques, partly to fill that gap. It is a pattern that is taking hold in other Shiite Muslim areas as the religious establishment challenges U.S. plans for transferring power to the Iraqis.

??We have told everyone from the start that only failure awaits the occupiers if they try to interfere in how we run our lives,’’ al-Issawi said. ??Occupation is humiliation, and we cannot accept humiliation. We never trusted the Americans and we never will.’’

The rise of a 22-year-old seminary student to such local prominence reflects vast political power attained by Shiite clerics in the nine months since Saddam Hussein’s ouster. Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Husseini al-Sistani, Iraq’s top Shiite cleric, has renewed his demand that a provisional assembly due to select a government in June must be elected, not chosen from regional caucuses as provided for in a Nov. 15 agreement between L. Paul Bremer, chief U.S. administrator in Iraq, and the Iraqi Governing Council.

Al-Sistani, 75, also demanded Sunday that an agreement on the status of U.S. forces after the transfer of sovereignty and the interim constitution being drafted now by the U.S.-appointed Governing Council must be approved by an elected national assembly. His demands threaten to delay the transfer of sovereignty to an Iraqi government by July 1, a major objective of the Bush administration in this U.S. election year. Al-Sistani is revered by most Shiites, who make up an estimated 60 percent of Iraq’s population.

Already, the United States has dropped one political plan for Iraq in the face of objections by al-Sistani, whose insistence that elected rather than appointed representatives draft the new constitution prompted the Americans to speed the timetable for handing over sovereignty and delay the drafting of a new national charter. Bowing a second time could make it appear U.S. policy in Iraq is subject to the demands of one elderly man, who hasn’t left his house since April, when Saddam’s regime collapsed, because of failing health and fears for his life.

However, Bush administration officials in Washington said Tuesday on condition of anonymity that the Nov. 15 plan may have to be altered. They insist the July 1 deadline for the transfer of sovereignty remains their goal.

The Iranian-born al-Sistani was virtually unknown outside Iraq until the mid-1990s, when two more senior clerics, including his mentor, died in quick succession. Now al-Sistani, who lives in a modest house on a dusty alley in the holy city of Najaf, has become a symbol of Shiite power, despite his proclaimed stand that his spiritual calling takes precedence over politics.

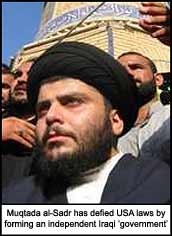

At the lower end of the Shiite clerical hierarchy, al-Issawi in Kut displays the energy and resolve of a much younger generation of robed Shiites intent on addressing problems big and small in their communities. Speaking at his office next to the Tigris River in Kut, 95 miles southeast of Baghdad, al-Issawi outlined activities undertaken by the movement led by maverick cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. Al-Issawi is al-Sadr’s Kut representative. They include a council to resolve tribal disputes, a security structure that posts sentries throughout the city after nightfall, rural development and a committee of local bureaucrats that meets every two weeks to review services.

Al-Issawi collects a Shiite religious tax called ??khoms’’ or ??fifth,’’ from well-to-do Kut residents and administers a court that sits once a month to settle domestic, property and inheritance disputes. ??The scope of jurisdiction of this court falls well below our expectations,’’ said the bearded al-Issawi, wearing a gray robe, a white turban and fingering prayer beads. Al-Issawi would like to see his court expand into criminal and other judicial matters.

Similar activities are carried out in other Shiite areas where al-Sadr, the son of a cleric killed in 1999 by suspected Saddam agents, enjoys wide support, including in Baghdad and Basra, Iraq’s second-largest city. They have been instrumental in softening the impact of the vast economic and security problems since Saddam’s ouster. In many cases, occupation authorities have sought, without much success, to push aside Shiite clerics to make way for their own prot?g?s, often secular-minded figures with a Western-oriented education but limited popularity.

Those problems were visible Tuesday in Kut. Long lines snaked from gas stations. Hundreds crowded a depot where scarce heating fuel was on sale. For a second straight day, hundreds of angry residents rioted to demand jobs. One person was killed and two were injured ? including a 22-year-old woman ? when Ukrainian troops opened fire to disperse the crowd.

??The Americans say they came to liberate us, but I must say their liberation has become a nightmare,’’ said 60-year-old Sajed Abed Abbas, the undertaker of a Shiite mosque. ??I was once a national weightlifting champion and I am now jobless and broke,’’ said 19-year-old Majid Zahi, pulling out the empty linings of his pockets.

The hold Shiite leaders wield over this city is evident in the huge murals depicting senior clerics ? both living and dead. ??The masses are more powerful than the tyrants,’’ declares fresh graffiti. ??The faithful are at the disposal of their religious leaders.’’

Published Saturday, January 17th, 2004 - 11:52pm GMT

Article courtesy of Associated Press

This is the print-ready version of Shiites Gaining Power In Post-Saddam Iraq

Hamza Hendawi

It was found in the Occupation Woes section of the World Crisis Web.

To view and post your views on the article in full go to http://www.world-crisis.com/analysis_comments/P361_0_15_0/