The Language of Empire

Renato Redentor Constantino

And so here we are, at the crossroads of another day, speechless and troubled by what is before us, so anxious to engage in a conversation with what ought to be, and yet so unaware of or indifferent to a past waiting to explain itself, to be heard, to be remembered.

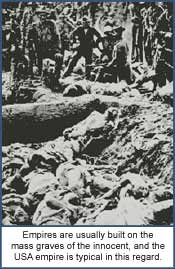

In its hunger for more resources, more markets, and more profit, the Imperial abmbition is no respecter of human suffering.

“You have to understand the Arab mind,” said Captain Todd Brown, a USA company commander with the 4th Infantry Division in Iraq, who had led his troops in encasing Abu Hishma in a razor-wire fence to contain the resistance suspected to be coming from the village. “The only thing they understand is force.”

Over a century ago, in a period of history that few Americans today can recall, another USA general uttered similar words.

It would take at least “ten years of bayonet treatment” to make Filipinos accept American rule, said Gen. Arthur MacArthur, even as, to deprive the “enemy” of popular support, USA troops herded whole Filipino villages into concentration camps ? precursors of the strategic hamlet used by the United States during the Vietnam War and the razor-wire fences now employed by the troops commanded by Captain Brown to enclose defiant Iraqi villages.

And what about Lt. Col. Allen West, an officer of the USA occupation army in Iraq, who was charged last year of “using improper methods to force information out of an Iraqi detainee,” Yahya Jhrodi Hamoody, an Iraqi policeman? In his testimony at the USA military?s version of a grand jury, West admitted that in the interrogation, after watching his soldiers beat the detainee on the head and body, he threatened to kill the policeman. West stated that he took Hamoody outside, pulled him to the ground and threatened to follow through his threat by firing his 9 mm pistol near the detainee?s head.

“I couldn?t remember how many shots were fired,” said West, who has since been called by members of the USA military Establishment as “an American who should be commended rather than court-martialed.”

For his act of torture, West was . . . fined $5,000, to be paid over two months, and reassigned to the rear detachment of the 4th Infantry division. The ?punishment? does not even affect West?s eligibility to receive retirement benefits and his pension.

“I want no prisoners, I wish you to kill and burn: the more you kill and burn the better you will please me,” said USA Gen. Jacob Smith over a century ago while his troops slaughtered civilians and Filipino revolutionaries defending the first republic in Asia and the freedom they had just wrested from Spain. When asked by a soldier to define the age limit for killing, Smith replied, “Everything over ten.” The troops under Smith, of course, followed the exhortations of their general to the letter.

Foreshadowing the “punishment” of Colonel West and the fate of Lt. William Calley, who was found guilty of leading USA soldiers in perpetrating horrors in the Vietnamese hamlet of My Lai and who served only four and a half months of his life sentence behind bars after which he was pardoned by Richard Nixon, General Smith was court-martialed for “conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline” and sentenced to ? an admonition.

The language of empire is often difficult to decipher but memory can be a good translator. “The boys go for the enemy as if they were chasing jackrabbits, said Colonel Funston of the 20th Kansas Volunteers over a hundred years ago as his men massacred Filipinos resisting the American invasion. “I, for one, hope that Uncle Sam will apply the chastening rod, good, hard and plenty, and lay it on until [the Filipinos] come into the reservation and promise to be good ?Injuns.?

And here is an American pilot talking about the joys of napalm while America was attempting to “liberate” Vietnam: “We sure are pleased with those backroom boys at Dow. The original product wasn?t so hot ? if the gooks were quick they could scrape it off. So the boys started adding polystyrene ? now it sticks like shit to a blanket. But then if the gooks jumped under water it stopped burning, so they added Willie Peter [white phosphorus] so?s to make it burn better. It?ll even burn under water now. And just one drop is enough, it?ll keep on burning right down to the bone so they die anyway from phosphorus poisoning.”

And here is USA Gen. John Kelly articulating his desire to improve the plight of wretched Iraqis in America?s invasion of Iraq in April 2003: “They stand, they fight, sometimes they run when we engage them. But often they run into our machine guns and we shoot them down like the morons they are . . . They appear willing to die. We are trying our best to help them out in that endeavor.”

Why do Americans keep asking “Why do they hate us so?”

In the origins of the relationship between the Philippines and the United States, a chapter known as the Philippine-American War, a chapter that began on February 4, 1899, and lasted an endless decade, Americans (and Filipinos) today may yet find what they have lost: the key to understanding the depravities of the present and, perhaps, their collective deliverance.

History does not always have to be a cruel teacher. The past preaches humility but it also teaches a certain kind of greatness. When Americans are ready to ask the question, “Why have we learned so little?” they will see hands extended to them waiting to be grasped; people elsewhere eager to tell them, in Arundhati Roy?s words, “how beautiful it is to be gentle instead of brutal, safe instead of scared. Befriended instead of isolated. Loved instead of hated.” Folks waiting to whisper in their ears, “Yours is by no means a great nation, but you could be a great people.”

Published Wednesday, February 25th, 2004 - 09:52pm GMT

Article courtesy of ABS CBN

This is the print-ready version of The Language of Empire

Renato Redentor Constantino

It was found in the Empire Abroad section of the World Crisis Web.

To view and post your views on the article in full go to http://www.world-crisis.com/analysis_comments/P438_0_15_0/